Retirement has always been treated as a predictable finish line: decades of work followed by a period of stability financed by savings, Social Security, and, for some, private plans. But this narrative is rapidly fragmenting. As the United States ages, retirement is consolidating itself as one of the country’s most relevant economic forces and, at the same time, one of the most unequal.

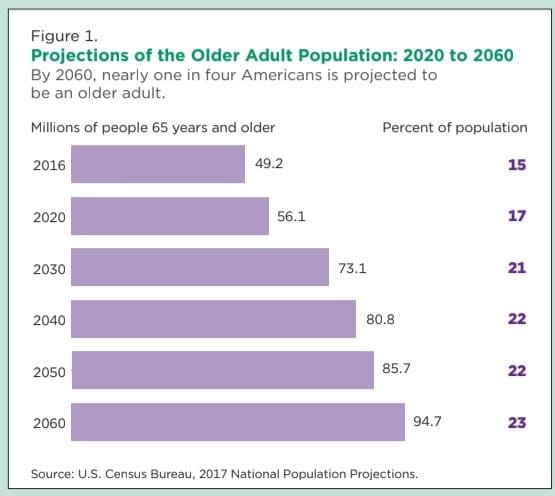

The numbers make this clear. By 2030, one in five Americans will be 65 or older. In 2034, for the first time in history, there will be more elderly people than children in the country, according to the U.S. Census. In 2026, this demographic transition will no longer be a distant projection, but a concrete reality, with profound impacts on the labor market, savings systems, public spending, housing, and, above all, the cost of aging with dignity.

The problem is that this aging does not happen uniformly. While some Americans enter retirement with record levels of savings and financial assets, others face rising healthcare costs, limited coverage, and a real risk of impoverishment. Retirement, like the rest of the economy, has come to reflect a structural divide.

Seven numbers help explain how this scenario is being shaped and why 2026 may mark a turning point.

The retirement age keeps rising

Retirement is happening later. According to the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, the average age at which men retire has reached 64, about three years higher than in the mid-1990s. Among women, the change has been even more pronounced: the average age rose to 62.6 years in 2024, up from approximately 55 years in the 1960s.

Part of this shift reflects real gains: better health, longer life expectancy, and greater female participation in the labor market. But there is also a less positive factor: many workers simply cannot afford to stop.

Even the moment of claiming Social Security benefits is being delayed. The average claiming age has increased by about two years since the 1990s, a trend that persisted even through the pandemic. Experts expected the health shock to lead older workers to retire earlier, but that did not happen on a large scale.

Remote work played an important role. For skilled professionals, the possibility of continuing to work from home made delaying retirement more feasible. Still, this flexibility is not available to everyone.

Retirement has ceased to be a definitive event

Nearly 40% of people who receive Social Security continue working after claiming the benefit. For many, this is not a choice, but a necessity.

There are two distinct groups within this contingent. One is made up of lower-income workers, who claim benefits early and then supplement their income with part-time jobs. The other includes high-income professionals who continue working full time even after reaching full retirement age.

The concept of retirement has therefore become fluid. People move in and out of the labor market, adjusting their participation according to health, the economy, or family circumstances. In many cases, financial instability is the determining factor.

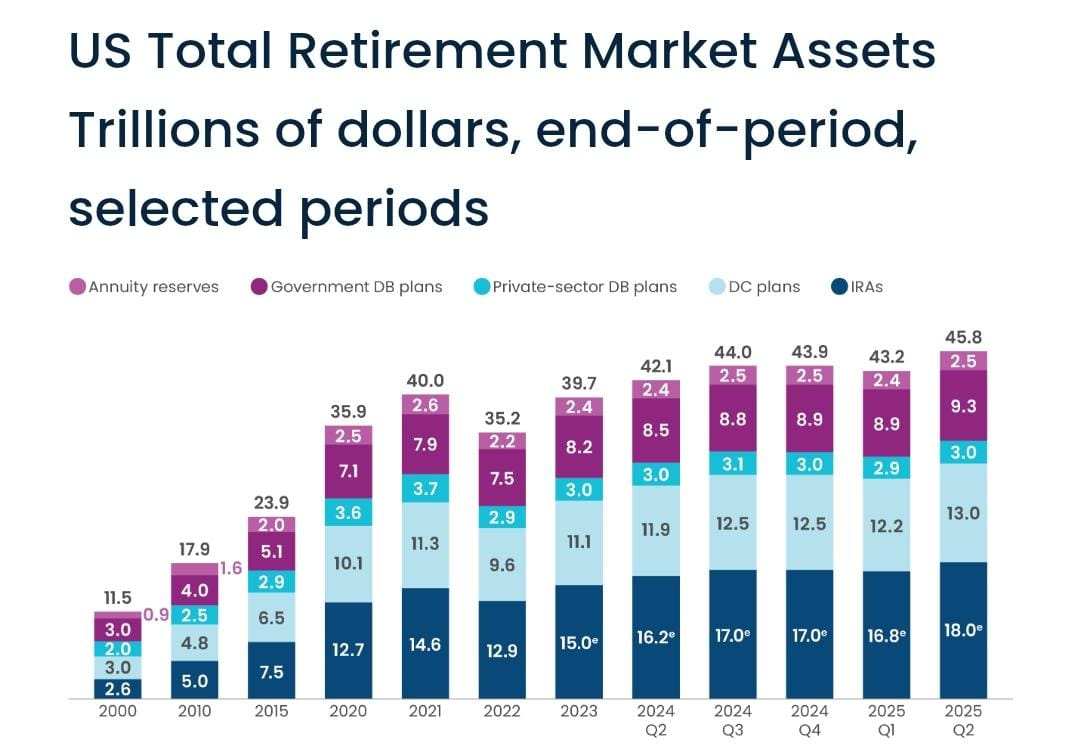

US$45.8 trillion in retirement assets and growing concentration

By mid-2025, there were US$45.8 trillion invested in retirement accounts in the United States, including 401(k) plans, individual retirement accounts (IRAs), pension funds, and annuities. This amount is nearly double what it was a decade earlier.

The growth reflects strong financial markets, greater participation in defined-contribution plans, and the maturation of the 401(k) system. But it also hides an important asymmetry: most of this increase is concentrated among middle- and high-income workers.

Over the past five years, IRAs have come to hold more assets than employer-sponsored retirement plans, driven by rollovers as baby boomers retire. This movement has intensified competition among employers, asset managers, and financial institutions to retain or capture these resources.

The 401(k) system became more efficient for those who have access

Today, 85% of workers who have access to a 401(k) plan participate, according to Vanguard data. The average savings rate reached 7.7% of wages in 2024, driven by mechanisms such as automatic enrollment and gradual escalation of contributions.

Combined employee and employer contributions reached an average of 12% of wages, up from 10.8% in 2015. In addition, target-date funds — which automatically adjust asset allocation according to age — have become dominant. In 2024, 84% of participants used these funds, and nearly 60% invested exclusively in them.

These changes made the system more resilient to shocks such as the pandemic, market volatility, and inflation. For those inside the system, savings tend to continue growing almost by inertia.

The other half was left out

The central problem is that only about half of private-sector workers have access to an employer-sponsored retirement plan at any given time. Small businesses continue to be the system’s main blind spot.

This gap helps explain why the median retirement savings for workers aged 55 to 64 was only US$185,000 in 2022. For lower-income workers, saved amounts have been declining. Racial disparities also persist: Black families hold, on average, only 14% of the savings of white families; Hispanic families, about 20%.

These numbers indicate that financial security in retirement remains, to a large extent, a privilege.

Higher maximum contributions, with new restrictions

In 2026, the contribution limit for 401(k) plans rises to US$24,500, with an additional contribution of US$8,000 for workers aged 50 or older. For those between 60 and 63, the extra contribution can reach US$11,250.

But there is an important change: workers earning more than US$150,000 will need to make these additional contributions exclusively through the Roth option, paying taxes now in exchange for future tax exemption.

The contribution limit for IRAs will be US$7,500, with an additional US$1,100 for older contributors.

These adjustments expand savings opportunities, but primarily benefit those who already have sufficient income to take advantage of the maximum limits.

Healthcare costs threaten early retirement

One of the most alarming numbers concerns healthcare. The end of expanded Affordable Care Act subsidies could increase annual premiums by about US$11,000 for early retirees.

People aged 50 to 64, too young for Medicare, are the most affected. A 64-year-old with income slightly above the subsidy threshold could pay, on average, US$16,500 per year for a basic plan, compared with just over US$5,000 currently.

Even for those already on Medicare, costs continue to rise. The standard Part B premium reached US$202.90 per month, nearly 10% higher than the previous year and 66% higher than a decade ago. Projections indicate it could exceed US$350 per month by 2034.

For lower-income retirees, these increases consume a significant share of the budget.

Long-term care: the greatest financial risk of old age

The average cost of a private room in a nursing home exceeded US$10,600 per month in 2024. Assisted living facilities cost about US$5,900 monthly, while full-time home care reaches US$6,500.

Despite this, according to surveys from the University of Michigan, nearly 85% of older adults say they expect to age in their own homes. In practice, many are not financially prepared to adapt their homes or hire long-term care.

Poverty among older adults is rising

In 2024, 15% of Americans over the age of 65 lived in poverty, a significant increase compared to 2021. It is the only age group in which poverty has grown in recent years.

Half of older adults cannot afford basic expenses, and 80% lack resources to face major unforeseen events, such as serious illness or the need for long-term care. Recent cuts to food assistance programs and Medicaid are likely to further worsen this scenario.

A divided future

The numbers reveal a retirement on two tracks. For some, it will be marked by autonomy, financial assets, and choices. For others, by prolonged work, insecurity, and rising costs.

In 2026, the central question will not only be when to retire, but who can truly do so.